After 40 years of fierce debate over oil and gas development in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), the Trump administration Aug. 17 cleared the way for the sale of drilling leases in the refuge – perhaps by as early as December of this year.

Hailed by Alaska’s governor and congressional delegation (all Republicans), and condemned by environmentalists, the move underscores the White House’s commitment to to American global energy dominance. CFACT Collegians were outspoken supporters of putting the area’s abundant energy resources to good use while safeguarding ANWR’s environment. The two goals are by no means incompatible.

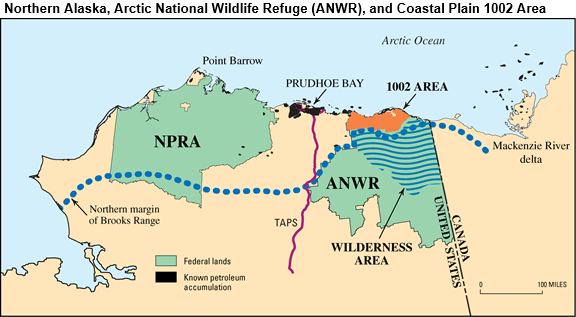

ANWR, which lies in northeastern Alaska and borders the Arctic Ocean, comprises some 19.3 million acres, of which the coastal plain – where drilling will be permitted – makes up 1.56 million acres, or 8.1% of the refuge. According to the Department of Interior, drilling pads, process facilities, and the roads needed for drilling will take up 0.01% of the refuge’s area.

How much oil is there in ANWR? Nobody knows for sure. But estimates run between 4.3 billion and 11.8 billion barrels, though seismic surveys have not been conducted since the 1980s. In any event, oil development in ANWR will pump billions of dollars into Alaska’s economy, and drilling could go on for 40 to 50 years.

Drilling in ANWR edged closer to reality with the passage of the 2017 tax cut which provided that the federal government must conduct two lease sales of 400,000 acres each in the refuge by December 2024. Interior Secretary David Bernhardt says the first lease auction could be held as early as December 2020, with actual drilling getting underway about eight years later. The Alaska Oil and Gas Association is less optimistic about the timeline, estimating that it could take 10 to 15 years before production gets underway.

Financing the exploration and extraction in ANWR’s coastal plain could be a problem. Several investment firms, including Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, Chase, and JP Morgan, have already announced they will not finance projects in ANWR, and other financial institutions are under pressure from environmental groups to follow suit. The current global oil glut, along with tepid demand and low prices, could also curb enthusiasm for drilling in ANWR.

Environmentalists and their allies in Washington have successfully block oil development in ANWR for four decades and vow to continue the fight in court. Former Obama EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy told the Washington Times (Aug. 18) that the Gwich’in tribes oppose oil development in the refuge and that Trump’s move “threatens the heart of the largest pristine wildland left in America.” But Interior’s Bernhardt points out that the Inuit people, who, unlike the Gwich’in, live in the refuge, favor energy development in ANWR.

“All permitted activities will incorporate required operating procedures and stipulated restrictions based on the best science and technology to ensure that energy development does not come at the expense of the environment,” the Interior Department said in a statement.