One of the pleasures of the just-ended Christmas season was hearing the late Nat King Cole’s splendid Yuletide favorite “Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire.”

America has a history with chestnuts – and with chestnut trees.

Standing as tall as 100 feet and measuring as much as 10 feet in diameter, the iconic American chestnut tree once dominated forests from Maine to Georgia and could be found as far west as Illinois with a few stands showing up in northern Louisiana. The chestnuts Nat King Cole sang about were so abundant that they were shipped by rail, mostly from Appalachia, to customers in cities throughout the country during the holiday season. This cash crop for many an Appalachian family was also prized by bears, squirrels, deer, wild turkey, many birds, small mammals, and passenger pigeons. European settlers marveled at a tree that had no equivalent in the Old World.

“The tree was also one of the best for timber,” notes the American Chestnut Foundation’s Virginia chapter. “It grew straight and tall, often branch-free for 50 feet. Loggers tell of loading entire railroad cars with boards cut from just one tree. Straight-grained, lighter in weight than oak and more easily worked, it was as rot-resistant as redwood. It was used for virtually everything – telegraph poles, railroad ties, heavy construction, shingles, paneling, fine furniture, musical instruments, even pulp and plywood.”

No more.

Curse of the Blight

Early in the 20th century, the tree began to fall victim to deforestation, a disease caused by root rot, and – most important of all – a blight brought over on Japanese chestnut trees. By the 1950s, the once-mighty American chestnut was functionally extinct, with only scattered, blight-resistant trees still standing. The blight alone is estimated to have killed between three million and five million chestnut trees.

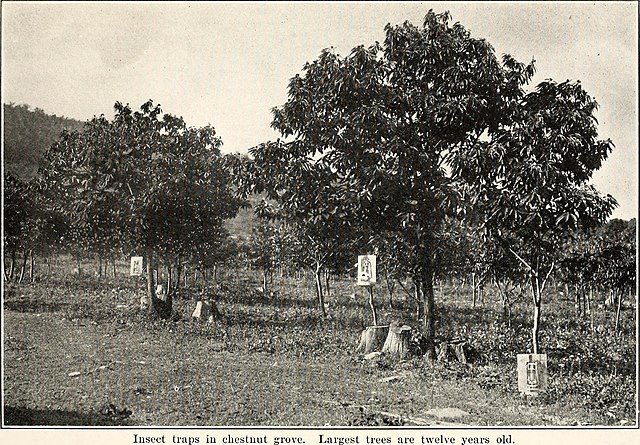

Over the decades, various chestnut enthusiasts have tried to bring the iconic tree back to life, with limited success. Now, advances in science are making that a realistic possibility, even if the two main approaches taken are in conflict. One strategy, favored by the U.S. Agriculture Department (USDA), the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Food and Drug Administration, would plant genetically engineered (meaning presumably bight-resistant) American chestnut trees in the wild to spread. If the agencies conclude that the benefits outweigh the risks, planting could begin in 2023. Currently, USDA permits planting in only a few selected areas, which are closely monitored by the agency. But these trees wouldn’t really be “American chestnuts,” because they will have been genetically engineered using their Japanese and Chinese cousins. Among other things, they would be about 20 feet shorter than the trees they are supposed to replace. There also is the fear that genetically engineered trees would spread rapidly in the wild and displace the few blight-tolerant surviving American chestnuts.

Another faction, the Wall Street Journal notes (Dec. 30, 2022), “has focused on reviving American chestnuts found in the wild after surviving the blight.” This process, which would take longer than genetic engineering the tree, would, if successful, restore the actual American chestnut species that the blight all but wiped out.

Conservation Biology Debunked

Regardless of which approach prevails, we now have the realistic hope that the American chestnut may soon flourish again in forests east of the Mississippi River. The saga of the American chestnut is illuminating for another reason. It belies one the tenets of conservation biology, which underpins modern environmentalism’s approach to the natural world, including dealing with endangered species and creating wildlife corridors.

One of the principles of conservation biology is that the loss of a “keystone species” will lead to the inevitable collapse of the ecosystem of which it was the dominant species. The American chestnut was nothing if not the dominant tree in the forests that comprised its habitat. Yet the demise of the American chestnut, however regrettable, did not lead to the collapse of the forests where it had been the top dog. Instead, nature adapted, and other trees took its place. If a blight-tolerant American chestnut does return to its old habitat, nature will adapt again, and make way for the majestic tree to reclaim its rightful position.

As the New Year begins, we raise a glass to the American chestnut!