Fed-speak, Alan Greenspan once explained, was about practicing the art of constructive ambiguity. Testifying to Congress as Fed chairman, Greenspan would resolve a sentence in a deliberately obscure way that made it incomprehensible, “but nobody was quite sure I wasn’t saying something profound when I wasn’t.”

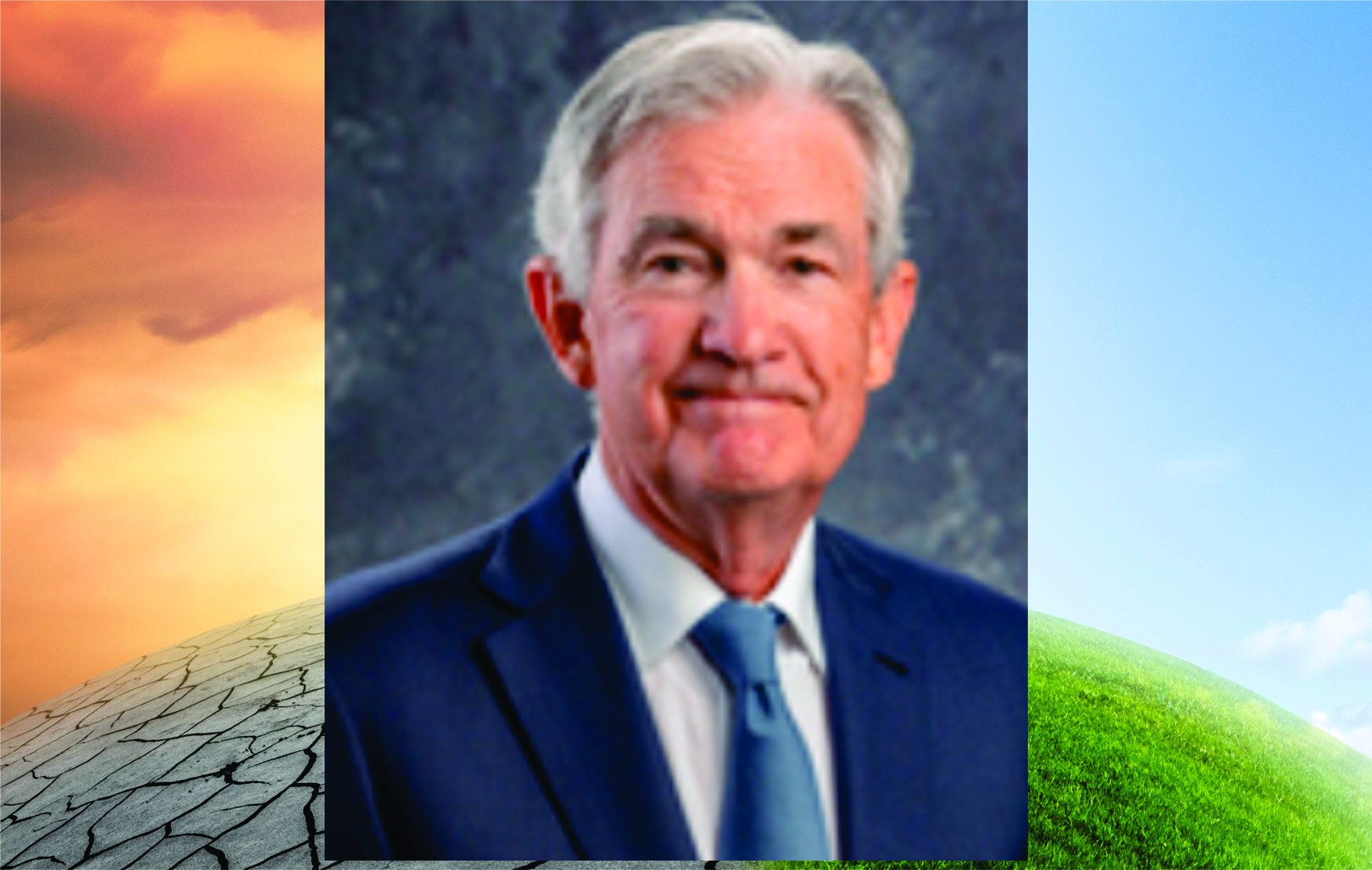

Speaking on Tuesday at a symposium on central bank independence in Sweden, Greenspan’s latest successor avoided ambiguity as he spoke about the Fed’s need to stick to its assigned policy goals of maximizing employment and price stability and not getting diverted to pursuing other objectives. “In a well-functioning democracy, important public policy decisions should be made, in almost all cases, by the elected branches of government,” Chair Jerome Powell declared. “It is essential that we stick to our statutory goals and authorities, and that we resist the temptation to broaden our scope to address other important social issues of the day.”

If that wasn’t clear enough, the current Fed chair noted that climate policies could have significant effects on companies, industries, regions, and nations: “Decisions about policies to directly address climate change should be made by the elected branches of government and thus reflect the public’s will as expressed through elections.” Without explicit congressional authorization, it would not be appropriate for the Fed to use monetary policy or its supervisory tools to promote a greener economy, Powell suggested. “We are not, and will not be a ‘climate policymaker.’”

But before supporters of limited government, separation of powers, and rolling back the administrative state stand up to applaud, they should remember that Powell has an indirect climate-policy tool: as part of its supervisory responsibilities, the Fed will require banks to understand and manage the financial risks of climate change. Yet at the same time, Powell would have us believe that the Fed’s supervisory decisions are “not influenced by political considerations.”

Climate “stress tests” are one of the principal tools used by the European Central Bank in furtherance of what its president Christine Lagarde openly proclaims as part of its mandate. “Our planet is burning and we central bankers could look on our mandate and pretend that it is for others to act and that we should simply be followers. I don’t think so,” Lagarde said at a June 2021 Green Swan conference of central bankers and regulators.

For its climate stress tests, the Bank of England uses the most extreme climate scenario developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. It then takes this projection about climate at the end of this century and telescopes eighty years of extreme climate change into three decades. The result is a physical impossibility. That a central bank believes it necessary to engage in such behavior demonstrates two things: that climate change does notrepresent a genuine threat to financial stability—if it did, the Bank would have used a plausible climate scenario—and that climate stress tests are indeed a tool of climate policy. Unlike the Fed, the Bank of England does have an explicit climate policy mandate. When he was Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak expanded the Bank’s remit to support the government’s goal of achieving “balanced growth that is also environmentally sustainable and consistent with the transition to a net zero economy.”

The Fed’s lack of a similar climate mandate proved no obstacle to Powell, however, when he spoke at the same Green Swan conference as Lagarde. The conference had been convened by the Network for the Greening of the Financial System (NGFS) to develop proposals for a more sustainable economy, financial sector, and society. “There’s a lot to like about climate stress tests,” Powell told the meeting. Not much constructive ambiguity there.

The NGFS is a club of central banks and financial regulators formed by the Banque de France in December 2017 on the second anniversary of the Paris climate agreement. Its aim is to strengthen “the global response required to meet the goals of the Paris agreement and to enhance the role of the financial system.” It also seeks “to manage risks and to mobilize capital for green and low-carbon investments in the broader context of environmentally sustainable development.” These objectives have no place in the Fed’s formal mandate.

Powell’s notion of an apolitical Fed tightly hewing to its congressional mandate is belied by the central bank’s decision to join the NGFS. Even more devastating to Powell’s claim of the Fed eschewing political considerations is the timing of that move: December 15, 2020, six weeks after Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump. The Fed cannot have it both ways. It cannot truthfully claim that its supervisory decisions are untainted by political considerations and remain a member of the NGFS. It was a mistake for the Fed to have joined the NGFS in the first place. If Powell wants to be believed, the Fed should quit the club.

This article originally appeared at Real Clear Energy