Something is going wrong with teenage girls. Horribly wrong. Zach Rausch and Jon Haidt have published a bomb of an article. Across the Anglosphere (and perhaps elsewhere) Gen Z girls are more anxious, more depressed, more likely to self harm and less happy, and not just a bit more, but in a seismic kind of way. Things are not exactly great for teenage boys either, but the trends are worst for girls and young women and most of the downturn started around 2012, uncannily in at least five different countries.

Rausch and Haidt make a compelling case that this coincides with the rise of smart phones and selfie-culture, and perhaps that is all the rocket-fuel we need. But the rise of the Glorious Victimhood Era of Woke was surely the guidance system that pointed a whole generation in a race to climb Mental Disability Mountain.

Teenage girls are magnets for fashion — not just in clothes but in ideas too. They may be collecting diagnoses like teenage boys collected football cards, but self-poisoning is not a sport.

The culture that acts like a teenage girl seems to be having trouble breeding healthy women.

Substack: After Babel

The Teen Mental Illness Epidemic is International

Zach Rausch and Jon Haidt

In sum, all five Anglosphere countries exhibit the same basic pattern:

-

-

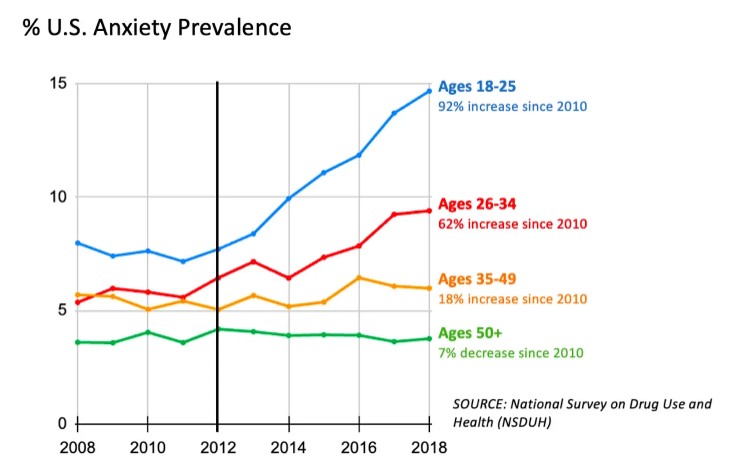

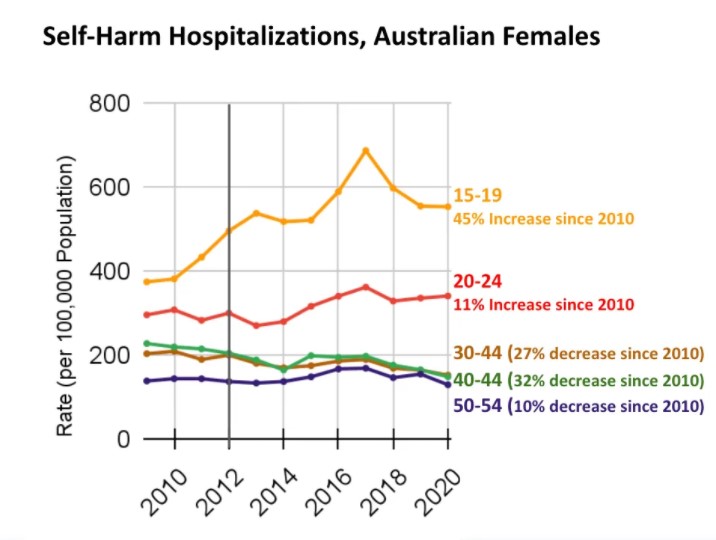

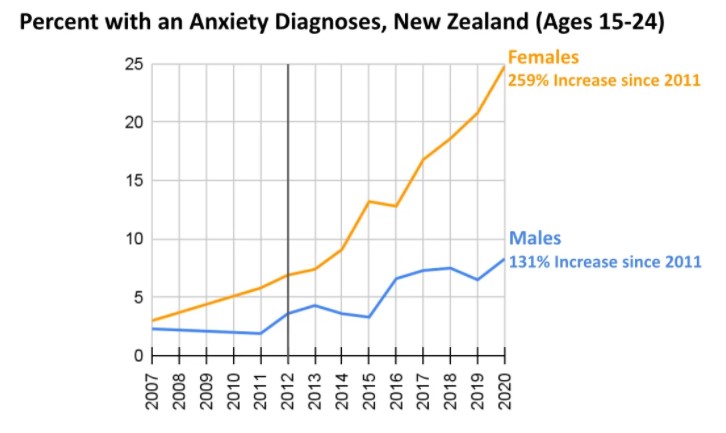

- A) A substantial increase in adolescent anxiety and depression rates begins in the early 2010s.

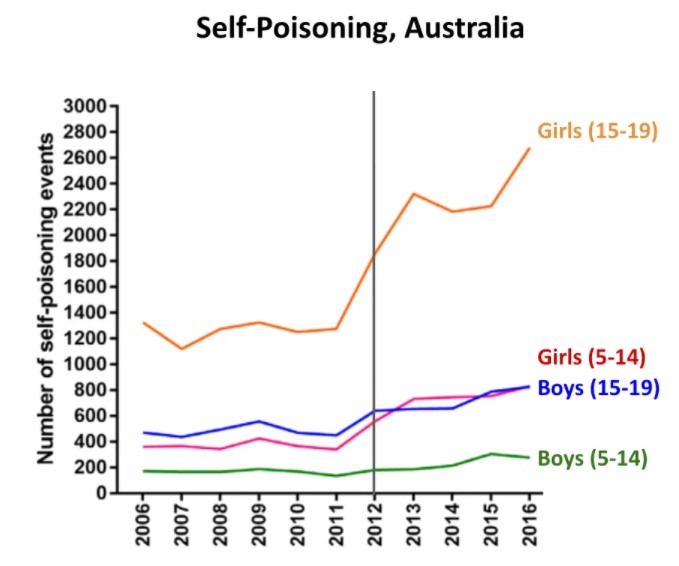

- B) A substantial increase in adolescent self-harm rates or psychiatric hospitalizations begins in the early 2010s.

- C) The increases are larger for girls than for boys (in absolute terms).

- D) The increases are larger for Gen Z than for older generations (in absolute terms).

-

Why did this happen in the same way at the same time in five different countries? What could have affected girls around the English-speaking world so strongly and in such a synchronized way?

At this point, there is only one theory we know of that can explain why the same thing happened to girls in so many countries at the same time: the rapid global movement from flip phones (where you can’t do social media) to smartphones and the phone-based childhood. The first smartphone with a front-facing camera (the iPhone 4) came out in 2010, just as teens were trading in their flip phones for smartphones in large numbers. (Few teens owned an iPhone in its first few years). Facebook bought Instagram in 2012, which gave the platform a huge boost in publicity and users. So 2012 was the first year that very large numbers of girls in the developed world were spending hours each day posting photos of themselves and scrolling through hundreds of carefully edited photos of other girls.

If you suddenly transform the social lives of girls, putting them onto platforms that prioritize social comparison and performance, platforms where we know that heavy users are three times more likely to be depressed than light users, might that have some impact on the mental health of girls around the world? We think so, but if anyone can offer another explanation that fits the graphs we’ve shown in this post, we’d love to hear it.

What Happened to Teens in the Five Anglosphere Countries?

There are 17 figures in the full post, graph after graph — all similar variations on young women in trouble. Women with anxiety, women harming themselves, in psychological distress, visiting psychiatry emergency departments, and generally feeling unhappy.

Perhaps shattering the glass ceiling isn’t all it’s cracked up to be? Perhaps the freedom to have meaningless one night stands and compete in the tinder date race, isn’t freedom at all?

Figure 3. Percent US Anxiety Prevalence. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

…

Percent US Anxiety Prevalence.

…

Figure 14. “Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have an anxiety disorder? This includes panic attacks, phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder?” New Zealand Ministry of Health, New Zealand Health Survey 2020.

..

Figure 13. Trends in intentional self-poisoning, ages 5–19 years, 2006-2016. Rates per 100,000. See 1.3.14 in The Coddling of the Australian Mind? Graph created by Cairns, Karanges, Wong, Brown, Robinson, Pearson, Dawson, & Buckley (2019), with text added by Zach Rausch.

…

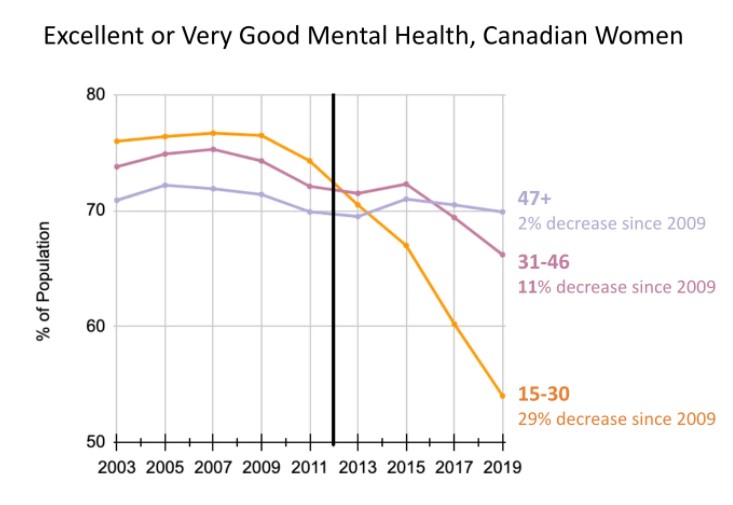

Figure 5. Excellent or very good mental health, Canadian women. Canadian Community Health Survey (2003-2019). See section 1.3.2 of The Coddling of the Canadian Mind? A Collaborative Review.

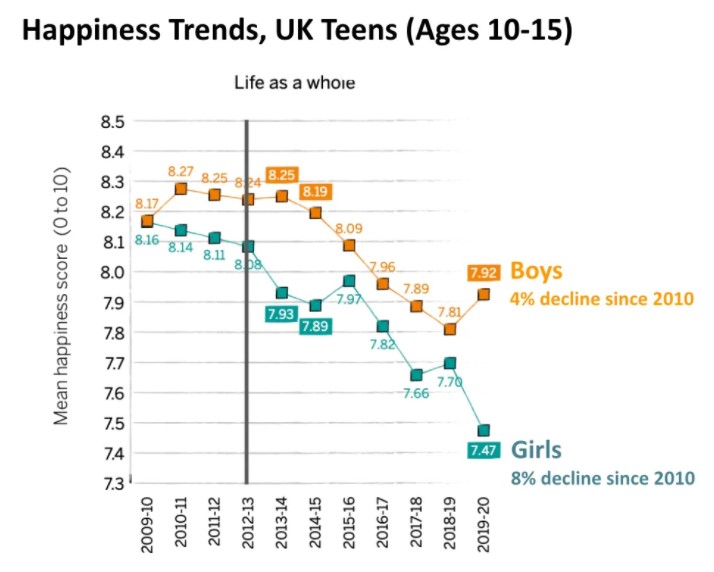

This graph is poignant — these girls are as young as 10.

Figure 8. Trends in children’s happiness with different aspects of life by gender, UK, 2009-10 to 2019-20, graphed in The Good Childhood Report (2022)—data from Understanding Society survey.

This article originally appeared at JoNova