Wildfires are being drawn inexorably into the climate change hysteria as dueling experts seek to explain the warm, dry weather we have experienced this year.

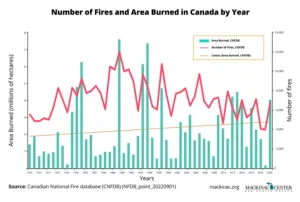

One recent article correctly moved past the climate concerns to explain how “The truth about forest fires goes up in climate-change smoke.” The author, Ross McKitrick, a professor of environmental economics at the University of Guelph, Ontario, gets it right when he describes how the number of wildfires and area burned have trended down over the past few decades in Canadian forests. He uses numbers from the Canadian Wildland Fire Information System.

“Wildfires have been getting less frequent in Canada over the past 30 years,” McKitrick writes. “The annual number of fires grew from 1959 to 1990, peaking in 1989 at just over 12,000 that year, and has been trending down since. From 2017 to 2021 (the most recent interval available), there were about 5,500 fires per year, half the average from 1987 to 1991.”

The overall number of fires shows a similar, declining trend in the U.S. over the past 30 years, but the acreage burned has increased.

A June 2023 Congressional Research Service “report” explains, “The number of annual wildfires is variable but has decreased slightly over the last 30 years.” The same report notes that “the number of acres affected annually, while also variable, generally has increased.” Research Service authors write, “Since 2000, an annual average of 70,025 wildfires have burned an annual average of 7.0 million acres. The acreage figure is more than double the average annual acreage burned in the 1990s (3.3 million acres).”

That Congressional report cites data from the current National Interagency Fire Center website, which only shows data back to 1983. This is further than the 30-year window considered by the Congressional Research Service report. But looking at the Center’s total available data does not change the overall picture appreciably.

The area burned is again variable, which is expected because significant fires can often escape and burn millions of acres in a dry year. Adding numbers from previous large burns can add some perspective.

The largest fire recorded in the U.S. was the Miramichi Fire in Maine, in 1825, which burned 3 million acres. Four of the ten largest fires reported in the United States occurred in or before 1910. The remaining six all occurred after 2000. The most devastating forest fire is the Peshtigo Fire, which occurred in October 1871 in Wisconsin. That single fire killed over 1,200 people and burned up to 1.5 million acres.

With several sources listing massive burns — more than one million acres — in the past two centuries, it’s interesting that the Fire Center’s data is limited to the past 40 years. For that additional information, the Internet Wayback Machine is a helpful resource. A look at one past iteration of the Center’s website shows that up until December 2020, the National Interagency Fire Center showed wildfire data going back to 1926. This additional data reveals a great deal about the nation’s wildfire history.

U.S. wildfires have dropped dramatically over the past century, both in number and total acres burned.

Despite the wide variability in the fire record, forest managers and fire modeling experts who are willing to speak out have argued that climate is and is not a major factor in wildfires. As the redacted data on the Fire Center’s website indicates, our perceptions of trends in fire behavior depend on when we start counting.

Published information on wildfires will often motivate trained foresters to reach out. McKitrick’s Financial Post article “prompted an interesting email…from an experienced forester,” he noted in a June 16 Tweet.

“As someone who works in forestry and has worked fires, and been evacuated due to fire, I have looked into the data, and it bothers me to no end how ‘the science’ is ignored.” They continue, “Climate change doesn’t make fires more intense, fuel loading does.”

The Mackinac Center has similar experiences. Our June piece on wildfires, “Only who can prevent forest fires?” explains, “Wildfire science confirms a basic fact: Dry weather tends to dry out materials that fuel and intensify wildfires. But climate change is not to blame for this year’s or any year’s wildfires.”

That is the case, even though “more and more, ostensibly settled climate science aches to point out that there’s nothing climate change can’t do. Whether you’re worried about increasing or decreasing temperatures, increasing or decreasing precipitation, increasing or decreasing wildfires, climate change appears to have you covered.” But “forest management policies play the key role in determining whether wildfires increase or decrease in number and intensity.”

We’ve received emails from foresters who say they agree with our forestry work. Refusing to allow active management and failing to suppress fires immediately have heightened fuel loading conditions. Heavy fuel loads ensure that, when a fire does start, and fire crews are not immediately able to stop it, it is likely to explode into an intense conflagration that burns everything.

These massive fires can effectively take areas back to the earliest of seral stages—bare mineral soil conditions, similar to when the glaciers retreated. From there, it can take decades for the land to transition from mineral soil back to grasses, to shrubs, and then to trees and forests.

People should be skeptical about the climate change hysteria that reemerges during every wildfire season. Instead, they should focus on active forest management practices, including harvesting, spacing, and thinning, as well as prescribed fires. These practices implemented prior to dry years would reduce fuel loading and lessen the likelihood of a major fire. This would do far more to protect forested lands than locking them up in preserves and hoping lightning never strikes.

This article originally appeared at Mackinac